Mental compulsions are repetitive, intrusive thoughts or mental actions that people with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) perform in an attempt to reduce anxiety or neutralize their obsessions. Unlike physical compulsions (checking, washing, or arranging)—mental compulsions are invisible and often harder to recognize.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) doesn’t always include physical compulsions like checking if the oven is off, washing your hands, or arranging objects in a perfectly straight line. Instead, you may experience what’s known as mental compulsions, where compulsions, which are repetitive behaviors or mental acts, occur entirely in your mind.

You might constantly replay past events in their mind, mentally “correct” or “undo” mistakes, or engage in repetitive thinking to reduce anxiety. For example, you might mentally count, pray, or say certain words over and over, believing that if you don’t, something bad might happen, or you may be responsible for causing harm.

While waging a hidden war within your mind can feel isolating, you’re not alone: “Almost everybody with OCD has mental compulsions,” says April Kilduff, MA, LCPC, LPCC, LMHC, a therapist and clinical trainer at NOCD. These are especially characteristic of what’s called Pure-O OCD, a subtype of OCD, but they can be present in any theme of OCD, and they can bring just as much distress as physical compulsions.

Let’s take a closer look at mental compulsions, how they’re different from physical compulsions, and exposure and response prevention (ERP) therapy—the most effective treatment option for OCD.

Find the right OCD therapist for you

All our therapists are licensed and trained in exposure and response prevention therapy (ERP), the gold standard treatment for OCD.

What are OCD compulsions?

OCD involves two primary symptoms—obsessions and compulsions—that disrupt your life, cause a lot of distress, or take up a great deal of your time. Obsessions are recurrent intrusive thoughts, sensations, images, feelings, or urges that cause distress.

Common obsessions include:

- Excessive worry about germs, leading to fears of getting sick or contaminating others.

- Concerns about accidentally causing harm to yourself or others.

- Intrusive thoughts related to sexuality and gender that cause anxiety or distress.

- Persistent, intrusive doubts and worries related to romantic or platonic relationships.

In response, someone with OCD performs compulsions to reduce anxiety, neutralize a thought, or prevent something bad from happening.

Some OCD compulsions are physical—you engage in them actively, and other people often see them happening. The most well-known example is compulsive handwashing: someone with OCD might feel the need to wash their hands five times in a row or else they’ll get horribly sick. Others with OCD might feel the need to confess their intrusive thoughts or check and recheck that their door is locked.

But physical compulsions don’t tell the whole story. Many people with OCD struggle in ways others can’t see, engaging in mental compulsions: thoughts or mental actions they feel a need to do over and over again to respond to obsessions or stop something bad from happening. In some ways, these can be even harder to handle than physical compulsions. “It’s one thing to decide ‘I’m not going to wash my hands,’” says Kilduff. “It’s another thing to try and decide ‘I’m not going to think about this anymore’ when that is what your brain wants to think about.”

Since they happen in your head, mental compulsions may go unnoticed by even your closest loved ones. Even you may not recognize exactly what’s happening. “People often don’t even realize they’re doing mental compulsions until we point out that they’re a thing,” explains Kilduff. In fact, mental compulsions can feel almost automatic.

Compulsions can look like:

- Excessive cleaning, hand-washing, or sanitizing to alleviate fears of contamination or illness.

- Mentally repeating prayers, phrases, or numbers, or mentally reviewing actions to ensure they were “correct” or harmless.

- Frequently asking others for reassurance or confirmation that things are “okay.”

- Repeatedly arranging or organizing objects in a certain order or pattern, driven by a need for symmetry or a fear of things being “wrong.”

What are mental compulsions?

Mental compulsions can occur with any type of OCD. In fact, a 2011 study involving a survey of roughly 200 people with OCD found that all participants reported at least one compulsion when mental compulsions and reassurance-seeking were included.

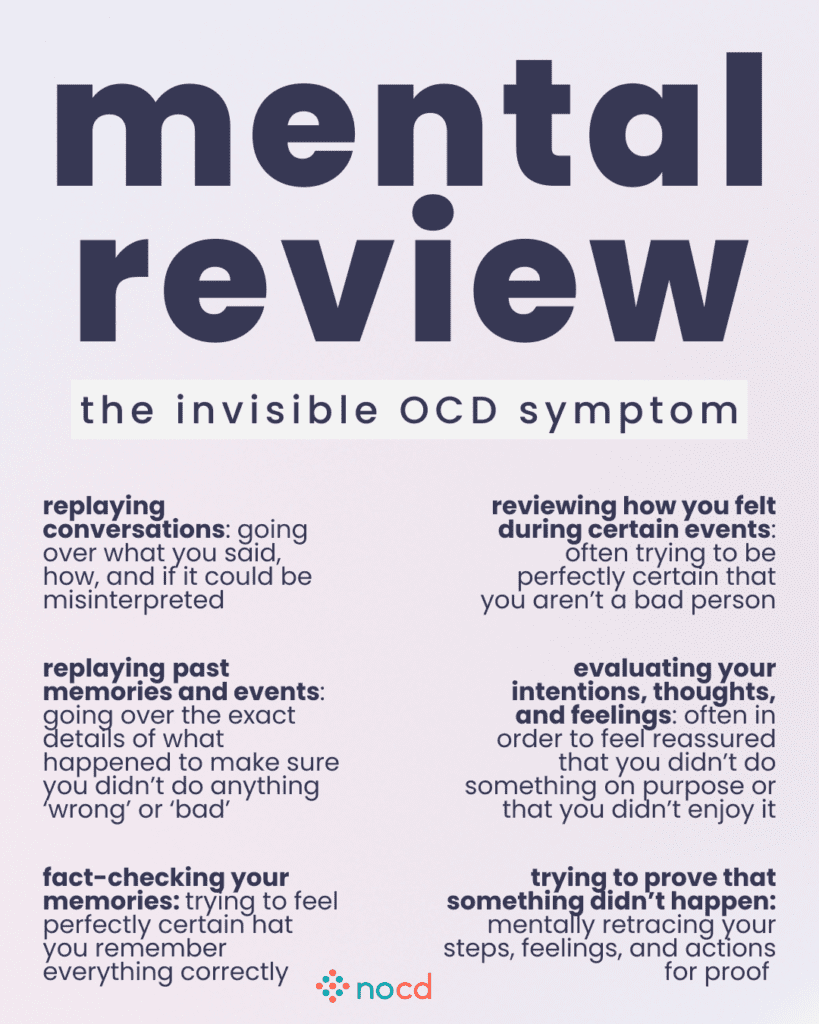

There are many different types of mental compulsions, but here are some of the most common:

- Compulsive prayer: While prayer is important to many people’s faith, it can also become compulsive. They may pray over and over again, try to pray “perfectly,” or restart a prayer if they get distracted.

- Counting: You might count anything in order to feel “just right” or drown out an obsession—steps, ceiling tiles, beats in a song—either out loud or in your head.

- Emotional checking: Compulsive checking doesn’t have to be physical. Emotional checking involves analyzing your emotions to make sure you’re having the “right” feelings.

- Memory hoarding: You might try to hang on to memories, thoughts, and experiences with perfect accuracy because you feel they’ll be crucial in the future.

- Mental reviewing: This could involve replaying a conversation you just had over and over again, or compulsively reviewing an event that happened years ago.

- Rumination: Often referred to as “overthinking,” rumination involves compulsively analyzing or trying to solve a perceived problem. It can be especially tough to identify, and can last for weeks at a time.

- Self-reassurance: Reassurance doesn’t always have to come from the outside. You might try to relieve your distress by reassuring yourself that your fears aren’t true, rather than asking others.

- Thought suppression: You might try to “drown out” an uncomfortable intrusive thought or distract yourself with something else.

Community discussions

What is Pure O OCD?

“Pure obsessional” OCD—often shortened to “pure O”—is a common but slightly misleading name for OCD that doesn’t involve any visible, physical compulsions. Instead, pure O OCD involves mental compulsions rather than physical ones. But just because compulsions aren’t visible doesn’t mean they aren’t there, and that’s why many experts consider pure O a misnomer.

Mental compulsions in common OCD subtypes

Contamination OCD

Obsessions: Thoughts like, “What if I touched something contaminated?” or “What if I accidentally spread germs to someone else?”

Mental compulsion: Continuously reviewing whether you’ve cleaned everything thoroughly or if you may have missed something important.

Harm OCD

Obsessions: Thinking, “What if I accidentally hurt someone?” or “What if I lose control and hurt someone I love?”

Mental compulsion: Reviewing your actions or thoughts to ensure you haven’t caused harm or may not cause harm in the future.

Religious (Scrupulosity) OCD

Obsessions: Thoughts like, “What if I’ve sinned without realizing it?” or “What if I’m not truly forgiven?”

Mental compulsion: Engaging in repeated mental prayers to “cleanse” yourself from perceived sins or negative thoughts.

Existential OCD

Obsessions: You may have thoughts like, “What is the meaning of life?” or “What if nothing matters or exists?”

Mental compulsion: Repeatedly analyzing or dissecting the same philosophical questions or concepts in an attempt to “figure out” the answers or make sense of them.

Relationship OCD

Obsessions: These may include thoughts like, “Am I really in love with my partner?” or “What if I’m not with the right person?”

Mental compulsion: Mentally repeating comforting thoughts or reassuring yourself that you do love your partner or that you’re with the “right” person, often replaying past experiences.

Can you have OCD without compulsions?

You can’t have OCD without compulsions. “Having compulsions is an actual requirement in order to get the diagnosis of OCD,” says Ibrahim. These include mental compulsions like rumination, mentally reviewing, checking, thought replacing, thought neutralizing.

Although pure O OCD may make it sound like you only experience obsessions without compulsions, that’s not the full picture. In reality, people with this type of OCD still engage in compulsions—they’re just often mental and not immediately visible.

How to treat mental compulsions

Exposure and response prevention (ERP) therapy is a specialized form of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) that was created specifically to treat OCD. In ERP, you’ll gradually and intentionally expose yourself to obsessions and anxiety while learning techniques to resist the urge to do compulsions. By consistently confronting these thoughts or situations without performing rituals, you learn that you can actually tolerate uncertainty and anxiety without relying on compulsions for temporary relief.

At the beginning of ERP, you and your therapist will begin with less anxiety-provoking situations, allowing you to slowly build your confidence in resisting compulsions. For example, if you have harm OCD and your obsessions are triggered around knives, you may be asked to look at a picture of a knife, without engaging in mental compulsions like distracting yourself, mentally repeating “I would never hurt someone,” or repeating a word that feels “safe.” Instead, you allow the discomfort and anxiety to pass on their own.

Since mental compulsions often seem to happen automatically, it can be hard to resist them at first. Your therapist might begin by asking you to interrupt mental compulsions by leaning into uncertainty. For example, if you start to ruminate on existential doubts, you could resist rumination by saying “there may or may not be meaning to life” and sitting with the anxiety you feel.

Bottom line

All compulsions, whether physical, mental, or a combination of both, can significantly impact a person’s life. While pure O OCD may seem like it only involves obsessions without visible compulsions, these mental compulsions are just as powerful and disruptive. Regardless of the OCD subtype you’re experiencing, working with an ERP therapist can help to create a personalized, structured plan for your unique symptoms.

Key takeaways

- Mental compulsions in OCD are hidden but impactful, involving repetitive mental actions like rumination, reassurance, or thought replacement to ease distress caused by obsessions.

- “Pure O” OCD is a common but misleading name, as even without visible compulsions, mental compulsions are present and can perpetuate the OCD cycle.

- Exposure and response prevention (ERP) therapy helps break the cycle of both physical and mental compulsions, empowering you to tolerate obsessions without acting on them.