If you believe your child might be showing signs of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), you’re not alone. OCD can show up early in life, sometimes even in toddlers as young as 2 or 3 years old. While it can be difficult to tell the difference between typical childhood behavior and potential OCD symptoms, knowing what to look for can help you take the proper next steps.

In this article, we’ll discuss the signs of OCD in toddlers and young children, what causes OCD in kids, and what you can do to help.

Signs of OCD in toddlers (ages 2 to 5)

Toddler OCD often presents differently from OCD in older children or adults. You might notice repetitive or ritualistic behaviors that go beyond everyday routines or preferences.

Signs of OCD in a 2-year-old:

- Insisting that objects be lined up in a specific way, and becoming very upset if disrupted

- Excessive hand-washing or asking others to wash their hands

- Tantrums when daily routines are altered in small ways

- Repetitive questioning or reassurance-seeking (e.g., “Will I get sick?”)

OCD signs in a 3-year-old:

- Repeating the same action over and over, such as tapping or touching

- Fear that something bad will happen if rituals aren’t completed

- Excessive checking (e.g., making sure the door is shut or toys are in a precise order)

- Avoiding things they used to enjoy, like touching pets or eating certain foods, due to a fear of contamination.

Signs of OCD in preschoolers (ages 4 to 5):

- Elaborate routines at bedtime, mealtime, or getting dressed

- Asking the same question multiple times, even after receiving an answer

- Distress or tantrums when a ritual is interrupted or when they can’t carry out a compulsion

Find the right OCD therapist for you

All our therapists are licensed and trained in exposure and response prevention therapy (ERP), the gold standard treatment for OCD.

Signs of OCD in 6 to 12-year-olds

Children in elementary and middle school may experience obsessions similar to those of younger kids—such as fears of contamination or harm, magical thinking, or a need for things to be symmetrical—but with more complex compulsions and internal distress.

Additional signs in this age group may include:

- Confessing “bad thoughts”: Your child may feel the need to confess intrusive or disturbing thoughts, believing that doing so prevents harm.

- Increased perfectionism: They might redo tasks like writing or cleaning until things feel “just right,” or get overly anxious about neatness, numbers, or specific routines.

- More complex intrusive thoughts: These can include worries about unintentionally causing harm or misbehaving in social settings.

Signs of OCD in teens (ages 13 to 19)

As children enter adolescence, hormonal changes and new stressors can lead to OCD symptoms focused on identity, morality, or sexuality.

Teens may experience:

- Intrusive thoughts about sex or sexuality that feel distressing or confusing

- Scrupulosity OCD, which centers around religion, ethics, or fears of being morally wrong

- Harm OCD involving fears of causing harm to others

- Avoidance of certain people or situations to prevent triggering intrusive thoughts

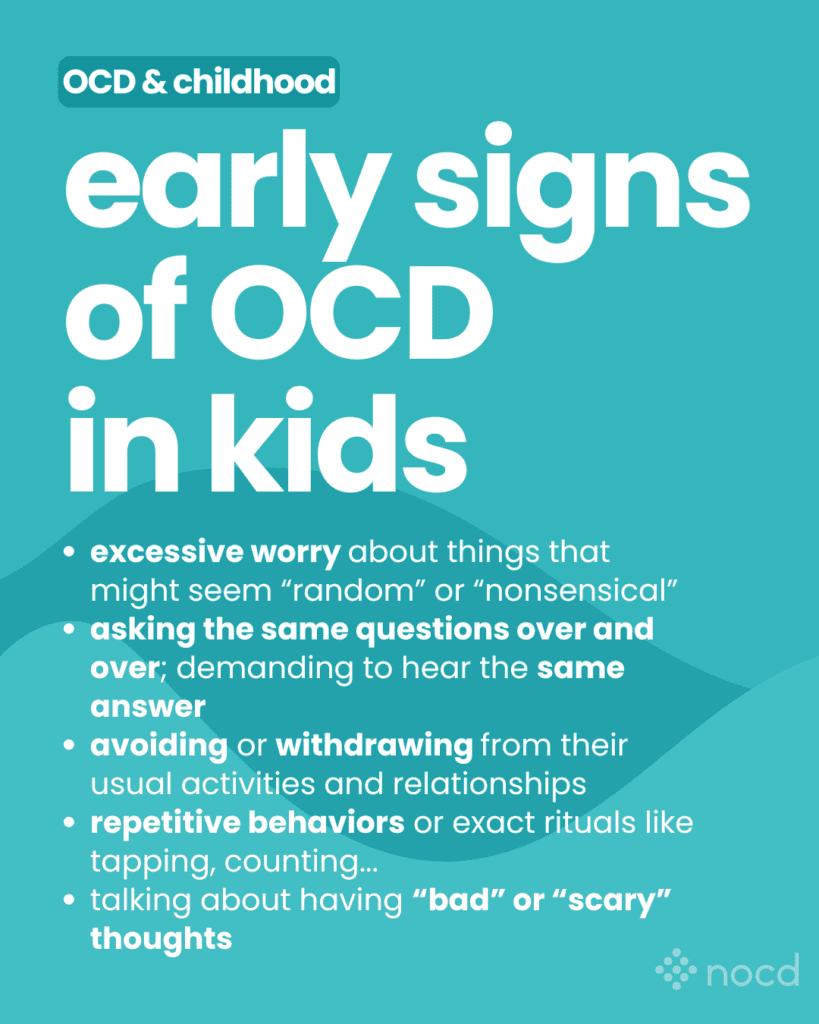

General signs of OCD in children

Across all ages, OCD is made up of obsessions (unwanted, distressing thoughts) and compulsions (repetitive behaviors aimed at reducing anxiety).

Common signs include:

- Fear of germs, illness, or harm coming to a loved one

- Repetitive behaviors, such as washing, checking, tapping, or organizing

- Needing things to feel “just right”

- Avoiding people

If your child seems trapped in rituals or overwhelmed by worries that don’t make sense to others, OCD may be the cause.

What causes OCD in children?

OCD isn’t caused by anything a parent did or didn’t do. It’s a complex condition with several contributing factors:

- Genetics: Children with a family history of OCD or other anxiety disorders may be more likely to develop it themselves.

- Brain differences: Research shows that certain brain circuits may function differently in people with OCD.

- Stressful experiences: Illness, trauma, or major life changes can sometimes trigger OCD symptoms.

- Infections (PANDAS/PANS): In rare cases, OCD symptoms may suddenly appear after strep or other infections due to autoimmune inflammation in the brain.

How is OCD in toddlers and children treated?

The best treatment for toddlers and children with OCD is exposure and response prevention (ERP) therapy. ERP is a specialized form of CBT proven to be effective for OCD. General CBT, if not tailored for OCD, can sometimes be unhelpful or even worsen symptoms. ERP helps children gradually face their fears without performing compulsions, teaching their brain that the fear will pass without rituals.

A recent landmark study by NOCD—the largest published study on OCD treatment to date—showed that virtual ERP therapy can significantly reduce symptoms—ranging from mild to severe—in children and adolescents. “We saw symptom reduction in about half the time that it takes for standard outpatient therapy,” says Jamie Feusner, MD, NOCD’s Chief Medical Officer and Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Toronto. “Another major finding was that symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress, which commonly co-occur with OCD, significantly improved as well.”

In some cases, especially if symptoms are severe, a pediatrician or psychiatrist may recommend medication in combination with therapy.

How parents can help

If you’re seeing signs of OCD in your toddler or child, here are a few things you can do:

- Avoiding feeding the compulsions: Reassurance, helping complete rituals, or making accommodations may seem helpful, but they actually make OCD stronger over time.

- Don’t punish or shame them: Their behavior isn’t a choice—it’s driven by anxiety.

- Seek professional help early: The sooner OCD is treated, the better the outcome will be.

- Stay calm and consistent: Structure and patience can reduce overall stress.

Frequently asked questions

What are the signs of OCD in a 3-year-old?

Repetitive behaviors like tapping, excessive handwashing, or strong resistance to changes in routine can be signs of OCD in a 3-year-old.

Can a 2-year-old have OCD?

Yes. While rare, signs of OCD can appear in toddlers as young as age 2. Early signs often include rituals tied to anxiety, not just habit.

What causes OCD in children?

Genetics, brain differences, infections, and stress can all play a role in childhood OCD.

How can I tell if my toddler’s rituals are OCD?

If your toddler’s routines cause them distress when interrupted or take up a lot of time, it’s worth consulting a mental health professional.

Bottom line

OCD can appear in toddlers and young children, often in subtle or surprising ways. Understanding the early signs—and knowing that effective treatment is available—can make a huge difference in your child’s life.

If you’re concerned about your child, please reach out to a qualified mental health professional—preferably an ERP therapist—with experience in pediatric OCD. Early support matters.

For parents concerned about costs and coverage for virtual ERP therapy, NOCD accepts most major insurance plans, providing coverage for over 138 million Americans.

Key takeaways

- OCD can begin as early as age 2 or 3, with signs that may look like extreme routines, fears, or rituals.

- Repetitive behaviors in toddlers—like tapping, excessive washing, or tantrums over small changes—may be more than typical childhood phases.

OCD in children is linked to factors like genetics, brain differences, stress, or in rare cases, infections such as strep (PANDAS/PANS). - Early treatment with exposure and response prevention (ERP) therapy can help kids manage OCD and reduce its long-term impact.