Like many of you out there, a few members of the NOCD team have tried a whole bunch of things for obsessive-compulsive disorder, or OCD. Many people struggle with obsessions and compulsions for years, and it is by no means abnormal to have searched far and wide for something that actually works.

All of us landed, eventually, in evidence-based treatment with an OCD-trained therapist. We were fortunate enough to live within a reasonable distance of specialists we could afford; though our treatment trajectories varied quite a bit, and there’s no such thing as a cure, we’ve all benefited greatly from exposure and response prevention (ERP) therapy.

But… the path was neither simple nor easy for anyone on our team. That’s why I’ve been going around the NOCD office and gathering thoughts about some of the things we tried before we learned about — and began — ERP therapy with OCD specialists.

Yep, we all did a lot of this. It’s only natural to start by searching on the internet when you have no idea what’s happening, and it’s tempting to keep going back whenever your anxiety really flares up (this is why OCD specialists tend to view Googling as a compulsion).

As a NOCD team member put it: “Googling gave me a source of comfort when I was too afraid to talk with anyone about what was going on. But it also ended up preventing me from finding more useful ways to deal with the problem. It was like getting fast food when I needed to learn how to cook healthy meals.”

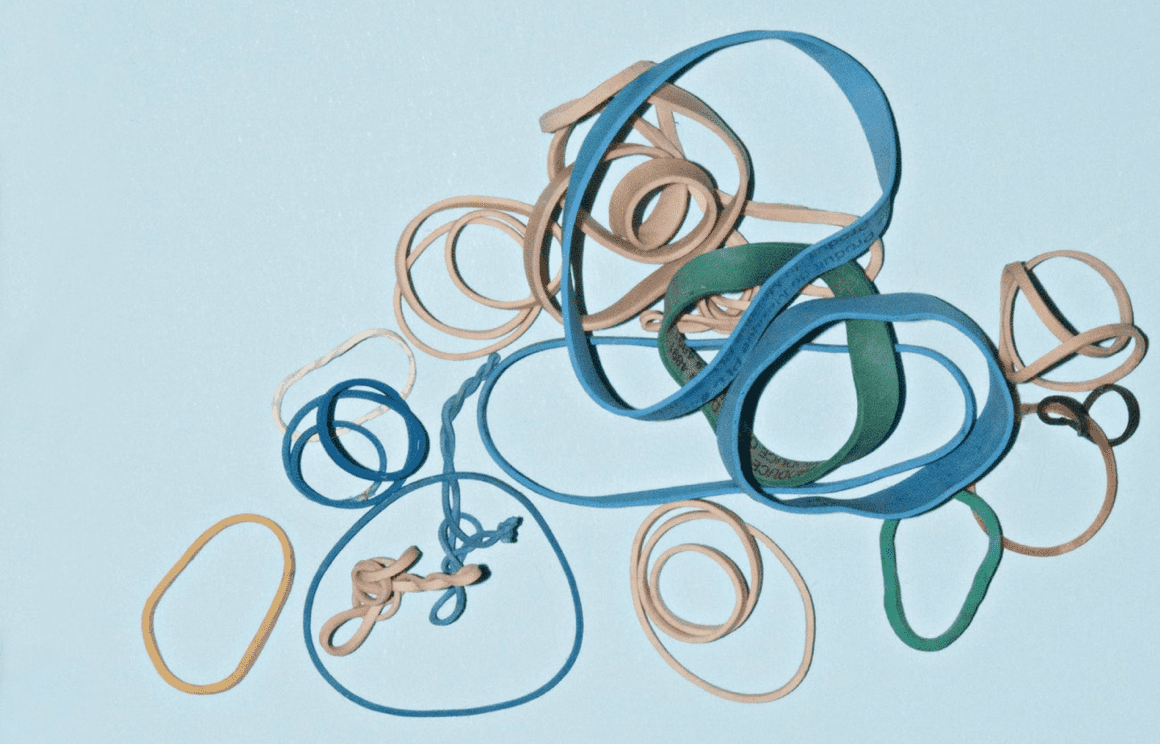

Snapping a rubber band

The rubber band trick is kind of old school, and has mostly fallen out of favor in the OCD treatment community. The idea: by snapping a rubber band on your wrist whenever you notice yourself obsessing you can bring yourself back into the moment and respond to the thought differently.

But this approach is no longer recommended because “thought stopping” isn’t useful, and can even be harmful, based on research. This may be because snapping your wrist makes you pay more attention to your thoughts, which is the opposite of what OCD treatment aims to do.

As a NOCD team member put it: “My first therapist told me to go around snapping a rubber band on my wrist all day. It wasn’t helping, and it seemed kind of weird to be inflicting a small amount of pain on myself whenever I was obsessing. It didn’t feel like a very advanced way of improving my psychological wellbeing.”

Avoidance

Netflix, video games, excessive sleeping, overexercising, drinking, drugs, texting, social media, and so on: the possibilities for avoidance are endless. Not to mention the most common form of avoidance—simply staying away from any situation that brings your obsessions to mind.

We all “tried” avoidance in the sense that it took us a while to even want to get OCD treatment. If we could’ve successfully gotten around the problem without the hard work, avoidance would’ve been helpful. But, like Googling, avoidance keeps you from getting the help you need. Depending on its exact nature, it can be harmful to your physical and mental health in other ways too.

As a NOCD team member put it: “Over time, I noticed that the activities I’d always enjoyed, like watching movies, had become compulsive for me. There was nothing quite like that escape from my most disturbing thoughts, especially when I’d spent the whole day struggling with them. But the OCD always caught up with me, and eventually I realized I would need to learn some strategies that didn’t involve my phone or laptop.”

Exercise

Exercise is generally a good thing, and people with OCD benefit from exercising just like anyone else. But this is a tricky one, because a “healthy” amount of exercise can easily slide into something else. Especially with something like OCD, where behaviors that relieve unwanted feelings transform pretty easily into compulsions. Moderation is hard to define, but being conscious of the way you’re using exercise, cutting yourself off after a pre-set amount of time, and taking regular days off are smart first steps.

As a NOCD team member put it: “For me, it’s important to think of exercise as a regular part of my lifestyle and a way to make sure I’m healthy and resilient, rather than a means of getting rid of my feelings. Getting reliable relief from stress and tension is one of main reasons I work out, but I have to make sure I’m exposing myself to imperfection here just as I do in other parts of my life. I’ve learned to exercise without it becoming a form of avoidance (or doing it until my physical health suffered), but it took a while to find this balance.”

Therapy

When most people think of therapy, they picture someone sunk into a comfortable couch, within reach of a Kleenex box, talking through problems while their therapist takes notes. This is what most therapy looks like, and it can be very helpful. Having a productive relationship with a good therapist — someone who’s experienced, empathetic, and knowledgeable — can work wonders for overall mental health. Specific therapeutic disciplines, like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), can be especially effective for mood disorders, anxiety-based disorders, and other conditions.

Because most therapy works in this way, most people start here. And it’s important to know that doing any kind of therapy is a great step. But some forms can actually worsen OCD symptoms by making thoughts seem more important and providing reassurance. ERP is specifically designed for OCD and related disorders, and works directly on compulsions — the part of OCD that you can control.

ERP is most effective when the therapist conducting the treatment has experience with OCD and training in ERP. At NOCD, all therapists specialize in OCD and receive ERP-specific training. I encourage you to learn about NOCD’s accessible, evidence-based approach to treatment.

As a NOCD team member put it: “There’s no denying the comfort I felt at having a compassionate, attentive listener each week. And I did gain a lot from working with my first therapist — we came up with plans for me to start exercising and sleeping more, talked through my family and relationship difficulties, and got me back on track. But after a year I realized the OCD part of my mental health wasn’t getting better, and asked for a referral to an OCD specialist. This made a huge difference.”