October is OCD Awareness Month, and at NOCD, we raise awareness to spotlight three system-level improvements needed to end the mental health crisis within the OCD community.

We must improve the time it takes to properly diagnose people with OCD, increase access to OCD specialists, and ensure people with OCD have always-on support when their provider isn’t available.

Our motivation is fueled by lived experience, myself included:

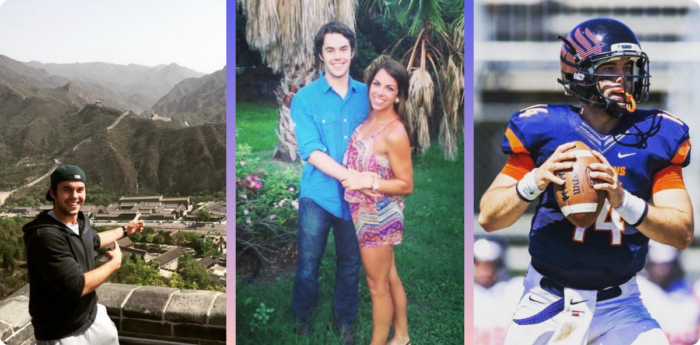

I went from being an award-winning quarterback at a small Texas college—doing well academically, athletically, and socially—to being housebound within six months. Untreated OCD, repeatedly misdiagnosed as anxiety and depression, brought my life to a grinding halt.

My turning point came when I discovered others online describing the same fears and safety-seeking behaviors I was experiencing. That was my lightbulb moment: what I had likely wasn’t just anxiety or depression—it was anxiety and depression caused by OCD, a condition that’s ranked by the World Health Organization (WHO) as one of the top 10 most disabling conditions in the world.

When I learned OCD was very treatable with a specific type of behavioral therapy called exposure and response prevention (ERP), I began to feel hopeful again. That hope was short-lived. I quickly realized accessing an OCD specialist who delivered ERP was nearly impossible. When I first sought ERP, there was only one provider near me, charging $300 per session with a 7-month waitlist. Thankfully a family member helped me get in and I saw significant reductions in my OCD’s severity within a few months. But that’s when I realized the problem wasn’t just clinical—it was systemic.

I then had the idea to start NOCD, to fill the operational holes in the mental healthcare system that had caused me such suffering.

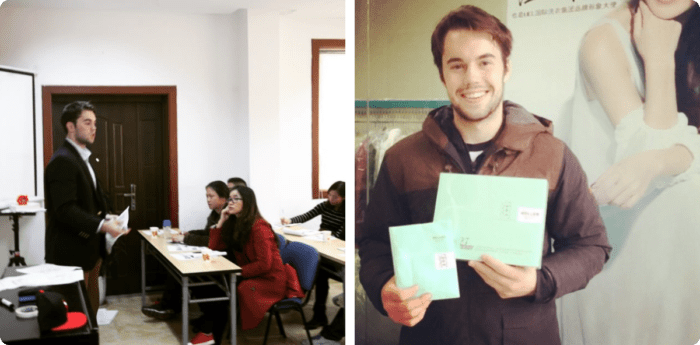

Since I had paused college due to OCD and didn’t have any money, I went to China to teach English, receive room and board, and buy time to prototype NOCD.

The plan worked for about six months, but building an early stage business abroad proved harder than expected. I returned to the States, re-enrolled in college at Pomona in California, raised angel investment, and started building NOCD with more support—all while continuing my football career and finishing my degree.

I spent whatever downtime I had building NOCD from my dorm room. I obtained feedback from OCD specialists, managed software engineers, built an initial team, and ran marketing campaigns. We gained traction, closed our first round of VC funding, and I graduated shortly after.

Since then, we’ve scaled NOCD to become the world’s largest behavioral health specialist and leader in OCD treatment. We’ve redefined OCD’s public perception alongside celebrity Howie Mandel, conducting millions of OCD-specialty therapy sessions across hundreds of thousands of members in all fifty states, and providing access to always-on self-help tools, peer communities, and messaging services when therapists aren’t around.

We’ve proven through our scaled results in OCD that a better mental healthcare system is definitely possible. Now, most people with OCD can get properly diagnosed within months, enroll in therapy within days, and pay only a copay.

Our mission won’t be complete, though, until we can affordably serve all people from Medicaid and Medicare populations, as well as those living with OCD internationally. I’m confident we’ll get there.

It’s important to note that my journey with OCD hasn’t always been upward. Even while building NOCD over the past decade, there were days when my OCD caused me to crumble inside, while I had to present outwardly as if nothing was wrong.

As OCD Awareness Month comes to a close, I’m sharing old photos from when I was struggling. Looking at me back then, you’d never know—I seemed happy, successful, well-traveled and surrounded by love. But like many people with OCD, I was fighting an exhausting internal battle that was invisible to everyone around me.

I want to remind everyone in our OCD community that even if the world can’t see your inner work, others who’ve been there can—and we’re in this together.

If you or someone you love is struggling, please know that help exists and there is hope. Getting better is possible.